Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Johannesburg, South Africa – On the night of June 27, 1985 in South Africa, four black men traveled together in a car in the south-east of the city of Port Elizabeth, now Gqeberha, in Cradock.

They had just finished community organization work on the outskirts of the city when officials of the apartheid police arrested them at a roadblock.

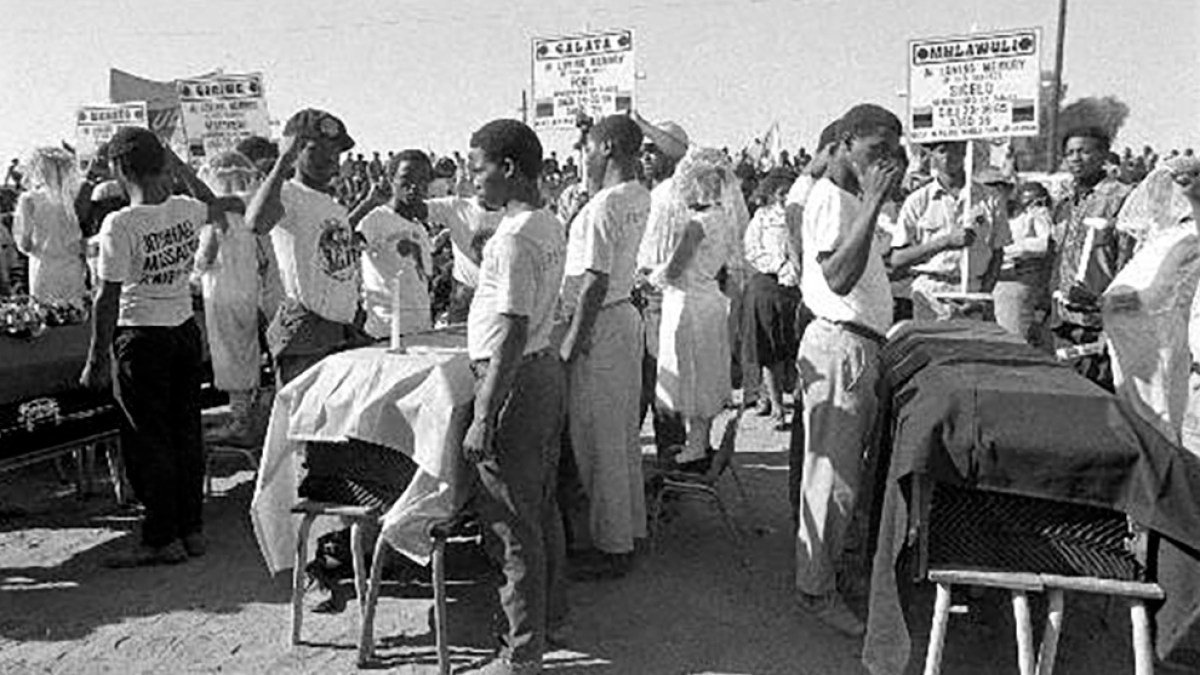

The four – Fort Calata teachers, 29, and Matthew Goniwe, 38 years old; Director of the Sicelo Mhlauli school, 36 years old; And Sparrow, 34, the rail workers – were removed and tortured.

Later, their bodies were found spilled in different parts of the city – they had been seriously beaten, stabbed and burned.

Police and the apartheid government initially denied any involvement in the killings. However, it was known that men were monitored for their activism against the exhausting conditions facing black South Africans at the time.

Shortly after, the evidence of a death mandate that had been issued for certain members of the group were disclosed anonymously, and later, it emerged That their killings have been planned for a long time.

Although there were two surveys on murders – both under the apartheid regime in 1987 and 1993 – none has led to the name or invoicing of any author.

“The first investigation was fully carried out in Afrikaans”, Lukhanyo Calata, Ford Calata’s son told Al Jazeera earlier this month. “My mother and the other mothers have never had the opportunity in any way to make statements,” deplored the 43 -year -old player.

“They were courts in South Africa in apartheid. It was a completely different period when it was clear that four people had been murdered, but the courts said that no one could be blamed for it.”

Shortly after the end of apartheid in 1994, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was created. There, the audiences confirmed that the “Cradock Four” were indeed targeted for their political activism. Although some former apartheid officers admitted to being involved, they would not disclose the details and were refused an amnesty.

Now, four decades after the murders, a new investigation has started. Although justice has never seemed closer, for the families of the deceased, it was a long wait.

“For 40 years, we have waited for justice,” Lukhanyo told local media this week. “We hope that this process will finally exhibit who gave the orders, who made them and why,” he said outside the Gqeberha court, where hearings take place.

As a South African journalist, it is almost impossible to cover the investigation without thinking about the extent of the crimes committed during apartheid – crimes by a regime thus determined to support his criminal and racist program that he brought it to the most violent and deadly end.

There are many more stories like those of Calata, many other victims like Cradock Four, and many more families still waiting to hear the truth of what happened to their loved ones.

Attend the legal proceedings in Gqeberha and watch the families reminded me of Nokhutula Simelane.

More than 10 years ago, I went to Bethal in the province of Mpumalanga to speak with his family about his disappearance in 1983. Simelane joined Umkhonto We Sizwe (MK), which was the armed wing of the African National Congress (ANC) – the liberation movement that has become a majority power party in South Africa.

As an MK business, she worked as a mail taking messages and parcels between South Africa and what was Swaziland.

Simelane was drawn to a meeting in Johannesburg and it was from there that she was kidnapped and held in police custody, tortured and disappeared.

His family says they always feel the pain of not being able to bury it.

In TRC, five white men of what was the special branch of the apartheid police, asked for an amnesty linked to the abduction of Simelane and the alleged murder.

Former police commander Willem Coetzee, who managed the security police unit, denied having ordered murder. But it was countered by the testimony of her colleague that she was brutally murdered and buried somewhere in what is now the northwest province. Coetzee previously said that Simelane had been transformed into a informant and had been sent back to Swaziland.

So far, no one has taken responsibility for their disappearance – not apartheid security forces nor anc.

The case of the Cradock Four also made me think of the anti-apartheid activist and member of the South African Communist Party, Ahmed Timol, who was tortured and killed in 1971 but whose murder was also covered.

Apartheid police said the 29 -year -old had fallen from a 10th floor window to the famous police headquarters from John Vorster Square in Johannesburg, where he was detained. An investigation the following year concluded that he had died by suicide, at a time when the apartheid government was known for its lies and its concealations.

Decades later, a second investigation under the Democratic government in 2018 revealed that Timol had been so badly tortured in detention that he could never have skipped through a window.

It was not until the time that the former officer of the security branch Joao Rodrigues was officially accused of the murder of Timol. The elderly Rodrigues rejected the charges and asked for a permanent stay of prosecution, saying that he would not receive a fair trial because he could not correctly recall the events at the time of the death of Timol, given the number of years that have passed. Rodrigues died in 2021.

Apartheid was brutal. And for people left behind, unresolved trauma and unanswered questions are salt in the deep wounds that remain.

This is why families like those of Cradock Four are always in the courts, looking for answers.

In his testimony to court this month, Nombuyiselo Mhlauli, 73 years old Sicelo Mhlauli’s wife, described the state of her husband’s body when she received her remains for burial. He had more than 25 injuries per stab on his chest, seven back, a cut on his throat and a missing right hand, she said.

I spoke to Lukhanyo one day before returning to court to continue his testimony during the hearing for the murder of his father.

He talked about how the emotional emptying of the process was – but vital. He also talked about his work as a journalist, growing up without a father, and the impact that it had on his life and his perspectives.

“There have been crimes committed against our humanity. If you look at the state in which my father’s body was found, it was a clear crime against his humanity, said Lukhanyo on the sixth day of the investigation.

But his frustration and anger do not end with the apartheid government. He has the ANC, which has been in power since the end of apartheid, partly responsible for taking too much time to adequately approach these crimes.

Lukhanyo thinks that the ANC betrayed the Cradock four, and this betrayal “cut the deepest”.

“Today, we are sitting with a company that is completely without law,” he told court. “(It is) because at the beginning of this democracy, we did not put the appropriate processes to say to the rest of society that you will be held responsible for the things you have done wrong.”

The grandfather of Fort Calata, the Reverend Canon James Arthur Calata, was the secretary general of the ANC from 1939 to 1949. The Calata family has a long history with the liberation movement, which makes it all the more difficult for someone like Lukhanyo to understand why he took the side so long to do justice.

The office of the Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development of South Africa, Mmoloko Kubayi, said that the ministry has intensified its efforts to do justice and closing at the long -term justice and closing for families affected by the atrocities of the Apartheid era.

“These efforts report a renewed commitment to restorative justice and national healing,” the ministry said in a statement.

The murders of The Cradock Four, Simelane and Timol are among the horrors and the stories we know.

But I often wonder all the names, victims and testimonies that remain hidden or buried.

The murders of countless mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, sons and daughters by the apartheid regime have not only the question of those who dealt with them, but of the conscience of South African society as a whole, regardless of normalization that the counting of the dead has become.

We do not know how long this new investigation will take. He should last several weeks, with a former security police, political figures and forensic experts.

Initially, six police officers were involved in the killings. They have all died since, but members of the Cradock four family say that senior officials who have given orders should be held responsible.

However, the state is reluctant to pay the legal costs of apartheid police involved in murders, which could slow down the process.

Meanwhile, while families are waiting for answers on what has happened to their loved ones and the responsibility of those responsible, they try to make peace with the past.

“I am alone, trying to raise children – children without father,” said Nombuyiselo in Al Jazeera outside the years since the death of her husband Sicelo. “The last 40 years have been very difficult for me – emotionally, and also spiritually.”