Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

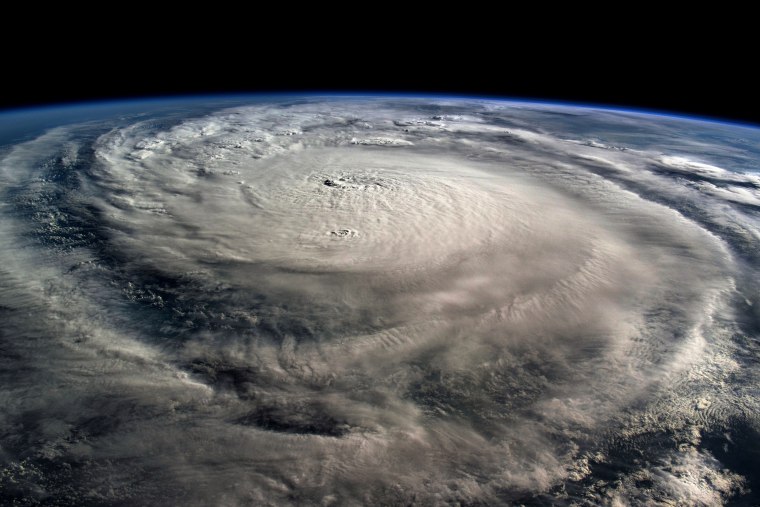

Forecastists should lose some of their strongest eyes in the sky a few months before the Atlantic Hurricane season culminated when the Ministry of Defense interrupts a key source of satellite data on cybersecurity problems.

The data comes from microwave sensors attached to three satellites in aging polar orbit operated for military and civil purposes. The data from the sensors are essential to the forecastists of hurricanes because it allows them to look through layers of clouds and in the center of a storm, where rain and thunderstorms develop, even at night. The sensors do not depend on visible light.

Lose data – at a time when the national meteorological service is Free up fewer meteorological balls And the agency is short of meteorologists due to budget cuts – will make the forecasters more likely to miss key developments in a hurricane, said several hurricane experts. These changes help meteorologists to determine the threat level that a storm can pose and therefore how emergency managers should prepare. The microwave data offers some of the first indications that the sustained winds are strengthened inside a storm.

“It is really the instrument that allows us to look under the hood. It is definitely a significant loss. There is no doubt about all the hurricane forecasts will be degraded because of this,” said Brian McNoldy, a hurricane researcher and senior research partner at the University of Miami, Rosenstiel School of Marine, atmospheric and earth sciences. “They are able to detect when a wall of the eyes forms in a tropical storm and if it intensifies – or intensifies quickly.”

Researchers think that rapid intensification becomes more likely in tropical storms while the oceans warm up due to the climate change caused by humans.

The three satellites are used for military and civil purposes through the Defense Meteorological Satellite program, a joint effort from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Ministry of Defense.

While hurricane experts said they were concerned about the loss of the tool, Kim Doster, director of communications at the NOAA, minimized the effect of the decision -making forecasts by the National Weather Service.

In an email, Doster said that microwave of the army “is a unique data set in a robust suite of forecasting and modeling tools in the NWS portfolio.”

Doster said that these models include data from geostationary satellites – a different system that constantly observes the earth about 22,300 miles from there and offers a point of view that seems fixed because the satellites synchronize with the rotation of the earth.

They also ingest measures of the Hurricane Hunter aircraft missions, buoys, meteorological balloons, terrestrial radar and other polar satellites, including the joint polar satellite system of the NOAA, which, according to her, provides “the meteorological observations of the richest and most precise satellites”.

An official of the American space force said that the satellites and their instruments in question remain functional and that the data will be sent directly to the weather satellite reading terminals through the DOD. The Navy Fleet Numerical Meteorology and Oceanography Center made the decision to stop processing this data and to share it publicly, said the manager.

The navy did not immediately respond to a request for comments.

Earlier this week, a navy division Researchers informed that he would stop processing and sharing data On June 30, and some researchers received an email from the digital meteorology center and oceanography of the Navy fleet, saying that its data storage and sharing program was based on a processing station that used an “end-of-life” operating system with vulnerabilities.

“The operating system cannot be upgraded, lays down a cybersecurity concern and presents risks for DOD networks,” said the email, which was examined by NBC News.

This decision will reduce the quantity of microwave data available for forecastists in two, said McNoldy.

These microwave data is also used by snow and ice scientists to follow the extent of polar ice, which helps scientists understand long-term climatic trends. Sea ice cream is formed from the water of the frozen ocean. It develops on the cover during the winter months and usually melts during the warmer periods of the year. Sea ice reflects sunlight in space, which cools the planet. This makes it an important metric to follow over time. The magnitude of the summer arctic sea ice is lower trends due to global warming.

Walt Meier, a principal researcher at the National Snow and Ice Data Center, said his program had learned the navy decision earlier this week.

Meier said satellites and sensors are about 16 years old. The researchers have prepared for them to finish, but they did not expect the soldiers to slip the data in a loop with little warning, he said.

Meier said the National Snow and Ice Data Center relied on military satellites for sea ice coverage since 1987, but will adapt its systems to use similar microwave data from a Japanese satellite, called AMSR-2, instead.

“It could certainly be a few weeks before getting this data in our system,” said Meier. “I don’t think that will undermine our data on the climate of sea ice in terms of confidence, but it will be more difficult.”

Satellites in polar orbit which are part of the Defense Meteorological Satellite program offer intermittent coverage of the areas subject to hurricanes.

Satellites generally zip around the world in a north-south orientation every 90 to 100 minutes in relatively low orbit, said Meier. The microwave sensors scan on a narrow strip of the earth, which Meier estimated at around 1,500 miles.

As the earth turns, these satellites in polar orbit can capture images that help researchers determine the structure and the potential intensity of a storm, if this is on their way.

“It’s often just lucky, you will get a very nice pass on a hurricane,” said McNoldy, adding that the change will reduce the geographic area covered by microwave scans and the frequency of the analyzes of a particular storm.

Andy Hazelton, a hurricane and scientific modeler associated with the Cooperative Institute for Marine & Atmospheric Studies of the University of Miami, said that microwave data is used in certain hurricane models and also by forecastists who can access close visualizations of data.

Hazelton said that forecasters are still looking for visual signatures in microwave data which often provides the first evidence that a storm quickly intensifies and strengthens force.

The National Hurricane Center defines rapid intensification as an increase of 35 or more sustained winds inside a tropical storm within 24 hours. The loss of microwave data is particularly important now because in recent years, scientists have observed an increase in rapid intensification, A trend probably supplied partly by climate change While ocean waters warm up.

A 2023 Study published the journal Scientific Reports found that tropical cyclones of the Atlantic Ocean were approximately 29% more likely to undergo rapid intensification from 2001 to 2020, compared to 1971 to 1990. Last year, The Hurricane Milton has strengthened from a tropical storm to a category 5 hurricane in just 36 hours. Part of this increase took place during the night, when other satellite instruments offer less information.

The trend is particularly dangerous when a storm, Like Hurricane Idaliaintensified just before hitting the coast.

“We have certainly seen in recent years, many cases of rapid intensification before landing. This is the kind of thing you really do not want to miss,” said McNoldy, adding that microwave data is “excellent to give the 12 additional hours of additional time to see the interior basic changes.”

Brian Lamarre, the former meteorologist responsible for the National Weather Service weather forecast station in Tampa Bay, said the data is also useful for predicting the impacts of the floods as an oil on the ground.

“This scan can help predict where precipitation and heavier precipitation rates can be,” said Lamarre. “These data are extremely important for public security.”

The hurricanes season begins on June 1 and ends on November 30. It usually starts to peak at the end of summer and early fall. Noaa forecasters have scheduled for a more busy hurricane season 2025 that typical, with six to 10 hurricanes.